The Vedbæk kayak club boats and paddlers had a long journey from north of Copenhagen to the southernmost tip of Norway. Several of us took the Oslo boat, then a long car journey, pausing for lunch at Lillesand.

We arrived late at our luxurious lodging at Øyhovda, and looked across to Farsund, about a kilometre across the water.

The landscape around Farsund is fjords cut by glaciers in hard rock.

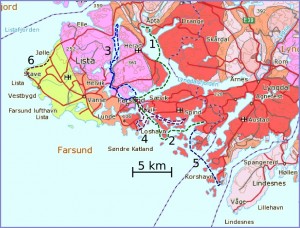

The view from a kayak on these waters is mostly geology. As the map below shows, our tours during this week were nearly all within the red shading which is granite and the pink shading which is charnockite, which is a similar hard rock of metamorphic or intrusive origin.

Our first day started with a road journey with trailer northward along a minor road which tunnelled three and a half km through the rock. We set the boats in at the head of Åptafjord. The fells rise to about 250 m in this region. From a kayak the view of steep rock walls with hanging woods in early spring leaf is dramatic.

It was surprisingly difficult to find soft deserted landing places so our first lunch was beside the jetty of a tiny harbour at Sæverland.

Unusually for the Vedbæk club outings, we twelve paddlers lived in luxury, with underfloor heated bathrooms and hot water in the shower. The evidence of Norwegian prosperity is everywhere; all the waterside houses were well cared for, and nearly all were empty at this early spring season when the trees where just bursting into leaf and the woodland flowers had just woken up. We took turns at preparing dinner, which required a paddle to the shops in Farsund.

Our second day started from the east, after a tour with the trailer to Bjørnevåg,We paddled west into the archipelago which extends south into open water. We cruised between the islands and again had trouble finding a lunch place. Eventually we perched beside a boat shed and watched a digger constructing a harbour wall of massive granite with impressive virtuosity. He nudged huge irregular granite stones into place so they fitted neatly together, held firm only by gravity.

There is less than half a metre tidal range here, so the walls were quite low. Some were extraordinarily finely jointed. Here is an elaborate harbour entrance with finely assembled dry stone walling.

The third day was almost entirely in the charnockite intrusion, a straight north south excursion along Framvaren, starting from our lodge. The northward paddle was easy and dramatic, between fells rising over 300 m on either side, and decorated with wind turbines. Here is the view up Logedalen – a deep sided dry valley.

Turning south, the wind was hard against us. Streams plunged steeply into the fjord.

We lunched at Listeid, where a paved road leads to a ramp where motor fishing boats can be hauled over a low pass into another fjord to give a nice round trip from Farsund.

This region is now dedicated to free time but there are traces of relatively recent subsistence agriculture, in the coppiced woodland and in the narrow stone walled fields reverting to woodland.

The fourth day the wind had abated somewhat so we ventured seaward to Loshavn. This town also was nearly deserted but had opulent architecture from the early nineteenth century. This wealth was amassed during the period of semi-legal piracy (the ‘kapertiden’) on English shipping during the Napoleonic war. After the English had seized the Danish fleet in 1807, the king (also of Norway in those days) gave permission for his seafarers to plunder the Brits, which they did with much success, using rowed cannon boats which could catch becalmed sailing ships by rowing up behind them and threatening the captain’s cabin with a substantial cannon.The evidence for the effectiveness of this technique is clear in the fine architecture of this small harbour, now one of Norway’s most cherished antiquities.

From the fort which guards the harbour one can see the lighthouse on Søndre Katland which guides traffic into Farsund.

The hardy paddlers braved the swell from the open sea to take a bold route past the lighthouse while some of us took a more sheltered route, exploring the sound north of Langøy, where we found an idyllic beach for lunch.

Just behind the camera is a small harbour with a white painted villa and red painted boat house, just as everywhere else where a small inlet provides shelter.

The fourth day started with a road trip east to Lyngsvåg. Then we paddled south east, still in the granite landscape completely unaltered since the melting of the ice sheet. The exposed skerries show typical granite weathering into huge blocks.

We passed through Korshavn, which lacks the charm of Loshavn but does have a cafe as compensation. The landing stages were too high for easy landing from a kayak so one has to assume that motor fishing is the main tourist activity around this coast.

We lunched in an inlet just east of Korshavn. Not a charming site, but the rocks shelved relatively gently, compared with much of the shoreline, which reached 30 m deep at one paddle length from the shore.

The return journey against the wind and choppy water over the fjord mouth was hard. As usual, almost everyone disappeared into the distance, dispersed over an area which would have made a rescue unsuccessful. They waited patiently round a sheltered headland, resting on their carbon fibre wing paddles while I caught up with my timber Greenland paddle and 78 years. Then they were off. I took a five minute rest, a drink and chewed some dried apricot. By that time all but one (my kind minder) were out of sight again.

The last day it rained all day. I gladly shared a walk over the entirely different flat landscape of Lista, starting at the lighthouse.

It was still a familiar granite boulder terrain, but underlain by schist rock which is less resistant to erosion and only appears in occasional outcrops on the coastline. The varied terrain and a western exposure which inhibits tree growth results in a rich plant life, though we were too early by several weeks to see it at its most abundant. The flat land supports the now defunct Farsund aerodrome which was heavily fortified in the war with Germany.

The abundant gun emplacements now afford shelter to the sheep, but they were also bored enough to follow us with an orchestra of tinkling bells.

This was a damp end to our tour. On the way home through Oslo some of us stopped off at the Fram Museum.

The light was dim and variable, imitating the polar night where the Fram drifted with the current under the leadership of Fritjof Nansen in 1893. It was technically very advanced, yet Nansen also was a kayaker. Here is one (or a model of) one of his two kayaks which were lashed together to sail on the arctic ocean.

Apart from being outdistanced all the time, I enjoyed the trip, and the company, which was fluent enough that I hardly needed to say a word for a week. Particular thanks to Hans Peter, who organised our luxurious lodging and guided our excursions with a light touch, to Claes, whose knowledge of nautical history enlivened our excursions, and to Bjørn and Mikael, who kindly kept me company at a cruising speed which would be fast for my English club.

Tim