|

The Lumen and the Lux |

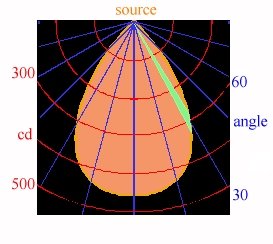

A light source emits with an intensity in a given direction that is measured in candela. Manufacturers of lamps and lamp fittings issue diagrams that show the distribution of light intensity in all directions.

The pale green ray shows that this particular wide angle spot light emits 300 cd in a direction 30 degrees from its axis. The luminous intensity directly forward is 460 cd.

If there is a museum object in the path of this beam we still know nothing about how much light it is receiving. The candela value is independent of distance. One can think of it as the emission from the lamp, which then loses interest in what happens to the photons it has ejected. We need a new unit for the light energy moving through space in the direction of our object.

This unit of invisible light in transit is the lumen.

The official definition of the lumen, the unit of luminous flux, is:

The luminous flux dF of a source of luminous intensity I (cd) in an element of solid angle dR is given by dF = IdR

In plain English: The flux from a light source is equal to the intensity in candela multiplied by the solid angle over which the light is emitted, taking account of the varying intensity in different directions.

The candela is a unit of intensity: a light source can be emitting with an intensity of one candela in all directions, or one candela in just a narrow beam. The intensity is the same but the total energy flux from the lamp, in lumens, is not the same. The output from a lamp is usually quoted in lumens, summed over all directions, together with the distribution diagram in candela, shown above.

Another quantity that is often quoted in catalogues is lumens per watt. The lumen is formally derived from the candela, which is based on light of a single wavelength. A practical lamp of many wavelengths has the lumen output calculated from the wattage emitted as radiation multiplied by the luminous efficiency at each wavelength, as described in the section on the candela. This value is more important than conservators generally realise. The low luminous efficiency of tungsten lights, much loved by exhibition designers, forces the installation of air conditioning in climates where it would not otherwise be necessary.

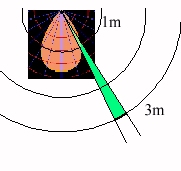

The diagram gives just the candela values emitted from the lamp. The exhibition designer needs to translate this into light energy falling on an object at any distance from the lamp. It is this energy that makes the object visible and that fades the dye. The energy density striking the object is given in lumens per square metre, generally known as lux.

The diagram gives just the candela values emitted from the lamp. The exhibition designer needs to translate this into light energy falling on an object at any distance from the lamp. It is this energy that makes the object visible and that fades the dye. The energy density striking the object is given in lumens per square metre, generally known as lux.

This value can easily be calculated from the diagram for a point source. The candela value given for 60 degrees, 300, corresponds to 300 lumens streaming out into a cone of one steradian, according to the definition given above. One steradian covers one square metre on the surface of a globe of 1 metre radius. If our object were at this distance it would receive 300 lumens per square metre. To deduce the value for any other distance, just use the inverse square law. At 3 metres away from the lamp the flux on a square metre has fallen to one ninth of 300 lumens = 33. The lux value is therefore 33.

Most objects are lit from more than one light source, or from extended sources such as diffusing panels. The arithmetic becomes more complicated. The reader is referred to the specialist literature. There are also computer programs to calculate the lux at any point which is illuminated from several sources.

Note that the illumination of an object in lux is not a measure of the photochemical damaging power of the light. As I wrote above, the lux is derived from the lumen, which is derived from the candela, which is defined for monochromatic light. The lumen flux from a practical light source is the sum of the energy in each wavelength band, multiplied by the luminous efficiency of that wavelength. The lumen value contains no information about whether the light flux is dominated by energy in the luminously inefficient, but photochemically efficient, blue wavelength or, as with a tungsten lamp, is largely provided by luminously inefficient but photochemically relatively harmless radiation at the red end of the spectrum. Furthermore, the lux value does not fully describe the visibility of the object, which depends on its ability to re-direct light into the viewer's eye. All one can say is that if one doubles the lux on an object, from the same type of light source, the photochemical damage will double. The lux is therefore a rather vague unit, considering its central significance in controlling the museum environment. Why do we use it? Well, internet is supposed to be an interactive medium, so I welcome comments from those more deeply versed in light than I. It seems that nearly everything to do with light measurement comes from attempts to install economic office lighting. Until recently, office folk shuffled pieces of white paper, perfectly light scattering, covered with black marks (occasionally red), perfectly light absorbing. For this activity the candela, lumen and lux, with the luminous efficiency curve lurking in the background, form a useful quantitative toolkit. This toolkit is incomplete in a museum. We should be putting more emphasis on measuring the incident radiation, weighted according to photochemical potency, and measuring the visibility of the object, as luminance.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.