Heat treatment

This is a conservation method in which the iron object is heated to

600 - 800 degrees C. This removes the substances which cause corrosion

and makes it easier to remove the rust down to the original surface. Conservators

have used this method for about a hundred years, with various modifications.

Nowadays, this method is used only for objects that show continuing corrosion.

The reason for the limited use is that heating alters the metal structure,

degrading the information available for metallurgical investigation. It

is not advisable to use this method for objects that contain other metals.

Tin, for example, will melt away at this temperature.

When this method is to be used for objects with important information

in the metal structure, small specimens are removed for metallurgical examination

before the object is heated .

The

left half of this picture is an etched cross-section showing two horizontal

layers of a piece of pattern welded iron, before heating. To the right

is a section after heating (field of view about 0.3 mm high). Notice the

markedly different microstructure in the two halves of the picture. (Pattern

welding is a technique for laminating thin sheets of iron of different

carbon content. When the finished object is polished, the slightly different

compositions show as a wavy pattern on the surface.)

The

left half of this picture is an etched cross-section showing two horizontal

layers of a piece of pattern welded iron, before heating. To the right

is a section after heating (field of view about 0.3 mm high). Notice the

markedly different microstructure in the two halves of the picture. (Pattern

welding is a technique for laminating thin sheets of iron of different

carbon content. When the finished object is polished, the slightly different

compositions show as a wavy pattern on the surface.)

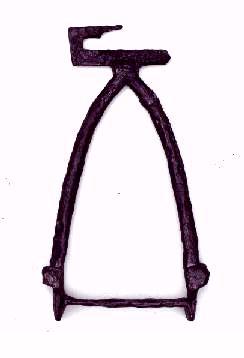

The stirrup on the left was heated by Rosenberg in 1914. It has acquired

a reddish colour, caused by oxidation during treatment. This appearance

was considered acceptable at that time.

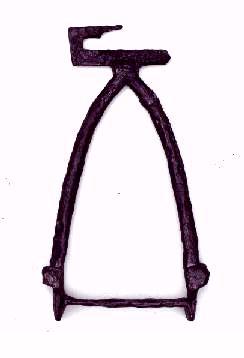

The stirrup on the right was re-conserved by heating in 1996. The oven

was flushed with nitrogen so that oxidation was prevented and the object

took on a grey-black colour.

Ornamentation: should it be revealed or allowed to remain concealed

in the rust?

After conservation, the archaeologist will want to investigate the decoration.

If the object is to be exhibited, there will be pressure to show a spectacular

object. Removal of the protective corrosion will, however, expose the object

to attack from air and pollutants.

When this stirrup from Hoby was discovered in 1893 the museum register

recorded: "Outside decorated with lines and curves inlayed with silver

and bronze." The rust was only partly removed and the object was coated

with varnish. In 1982 the archaeologists asked for the object to be cleaned

for exhibition, so that the inlay could more easily be seen. The conservator

dissolved the old varnish and then removed the superficial rust in a chemical

bath with ultrasound. After drying, the iron was treated with tannin, followed

by an acrylic varnish to inhibit corrosion. One seldom cleans stirrups

so thoroughly.

On to the next showcase...

The

left half of this picture is an etched cross-section showing two horizontal

layers of a piece of pattern welded iron, before heating. To the right

is a section after heating (field of view about 0.3 mm high). Notice the

markedly different microstructure in the two halves of the picture. (Pattern

welding is a technique for laminating thin sheets of iron of different

carbon content. When the finished object is polished, the slightly different

compositions show as a wavy pattern on the surface.)

The

left half of this picture is an etched cross-section showing two horizontal

layers of a piece of pattern welded iron, before heating. To the right

is a section after heating (field of view about 0.3 mm high). Notice the

markedly different microstructure in the two halves of the picture. (Pattern

welding is a technique for laminating thin sheets of iron of different

carbon content. When the finished object is polished, the slightly different

compositions show as a wavy pattern on the surface.)