The propeller driven aircraft of Air Corsica gave me a panoramic view of the coming adventure as it approached Ajaccio airport along the west coast of Corsica.

Cap Rossu is the orange lump. There are closer pictures later.

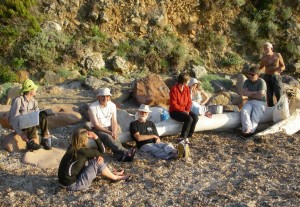

At the airport we encountered the one sure experience of travellers – waiting. This is most of the Danish team of six in the Bays Trophy (more on this later), the rest of the group is resting under a palm tree or behind the camera.

We were fetched by Cors’ Aventure (more on that outfit later) and provided with Prijon Seayaks and everything needed to paddle them.

Our starting point was Calcatoggio, north of Ajaccio. The second sure experience of kayak paddlers who have travelled far and dear for a week of adventure is that the weather will dash their plans.

The gale had started when we arrived and continued into the night. I wasn’t too upset because I wanted to see the land of Corsica as well as the coast. We had met the rest of the Trophy participants, all from France, and a mixed group set out along the dreary coast road, lined with the holiday flats that are spreading around the Mediterranean.

After a couple of km we diverted up a stony path to one of the ancient towers which were used to signal the approach of enemy ships by setting a fire on top. The island has over a hundred of these towers, each within sight of the next.

Photo by Jean-Philippe Levrel

The author is on the left, always recognisable in a flash photo by the glare from the reflective tape on his spectacles harness.

Some of us then continued through the low spiny scrub called maquis in France, following a return route parallel to, but far above, the coast road.

The flowering season was nearly over, the ground dry and dusty. I found the dusky red orchid Serapias but none of the insect-imitating orchids which I expected.

We followed a track whose stone walls were the only remaining evidence of past agriculture. The island is now almost entirely dependent on tourism. The path eventually descended past new holiday villas towards our campsite by the beach.

We had lost a day’s paddling, so the leader of the Bays Trophy, Claude, decided to move the kayaks by road to the next but one planned stop, because it would take half a day to transport the 16 kayaks in two journeys along the tortuous coast road.

By the time we had arrived at the beach of Arone the wind had abated but the swell gave some excitement to our test paddles with our hired boats.

The sun was beating down on the beach, though the air was cool. We fixed up a shady tarpaulin.

Now it is time to introduce Catherine, our local expert navigator and cook, employed by Cors’ Aventure. She was an important cause of the good humour of the participants because she ensured that it was less a kayak tour than a gastronomic adventure interspersed with relaxed kayak explorations of the highly indented and dramatic coastline.

Here she is presiding over lunch. Everything was done with a single burner, a vast deep pot, a shallow pan which fitted over the pot and a lid. Lunch was a cold mixture, dinner a warm mixture. I became familiar with the variety of traditional Corsican cuisine because my capacious seayak carried a variety of tins of beans and bottles of sauces, together with water barrels and bread. That was a disadvantage of packing all my own stuff into Easyjet hand baggage – there was plenty of space for food for the group.

After the test paddle in empty boats we retired to the beach cafe.

In the back row from the left are the leader of the French team and inventor of the Bays Trophy, Claude, the leader of the Danish team, Claes, and in the white hat, Catherine.

The purpose of this interlude was to allow time for the sun to set so we could enjoy our evening meal in confusing gloom and then wash up in total darkness. Fortunately, Claes, who had brought a complete ships’ chandlery of essential equipment, rigged up a lamp over the groundsheet, otherwise we would have been blinding each other with our eyebrow lamps.

By the end of dinner it was long past my usual bedtime, so I skip rapidly to the next day and the real paddling part of the tour.

We headed west towards Cap Rossu, the orange headland shown in the first aerial picture.

Corsica is mostly igneous rock, granite on this part of the journey, changing to basalt flows in the middle part, then granite again at the northern tip. Cap Rossu is rhyolite flow – this is the volcanic equivalent of granite.

The rhyolite flows alternate with pyroclastic layers, which are explosive deposits containing blocks of granite and rhyolite. This rock is penetrated by dark basaltic dykes.

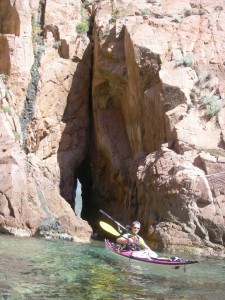

The rock formations weather into numerous caves and underground passages.

As we rounded the cape into the gulf of Porto the high central mountains came into view. These also are granite, as is much of the western side of Corsica.

The granite shows the classic signs of salt weathering, with holes scooped out as the salt spray migrates to the centre of each depression so that it concentrates there and splits apart the mineral crystals as the salt crystallises.

Our lunch breaks were generous in both food and time, which made the tour unusually relaxed and not at all tiring.

We continued along a continuously varied and always dramatic coast.

Our evening landing was at Porto. The campsite was a laborious 500 m trudge from the harbour but it was good to have a warm shower. The campsite is at the end of a valley which rises steeply into the interior. I suspended my Hennessey hammock from trees which give welcome shade in high summer but give no shelter from the cold katabatic wind descending from the snow covered mountains. I was barely warm enough in my minimalistic equipment and clothing.

The harbour at Porto is protected by an ancient tower, but looking to the east…

…we see the spreading apartments of the island’s tourist industry.

The daytime onshore breeze is also strong, as shown by the windblown vegetation west of Porto. The prevailing wind is also from the west. We were fortunate to have calm weather for the next few days.

At our lunch stop at Gratelle there was a rare exposure of traditional building technique. Dry granite blocks chinked with small stones.

The cliff scenery continued to intrigue with its grottoes and hidden passages.

We stopped for water at Girolata, an ancient settlement with a castle and the safest harbour on the west coast. Nevertheless, there is no road to Girolata and only a handful of permanent residents. At a stone circle once used as a platform for winnowing grain we chanced upon a local sage lecturing a small group of French tourists about the history of the place. He told fluent and dramatic tales of the ever changing ownership of the island, with defeats, victories and taxes. However, when the expert explained that Roman roads could be traced by the anti-malarial planting of Eucalyptus trees I began to suspect that his tales were free fantasy.

Here is an example of modernised vernacular – the cement block vertical extension is set with intermittent granite blocks. It looks fine, in contrast to the brutal cast concrete of much of the seaside building.

Here is the port and beach at Girolata. We paddled away to a nearby empty beach to camp.

Wild camping is officially forbidden but in practice it is tolerated. I try to be discreet. Here I am using two break-apart paddles to adapt my hammock to a treeless beach. The hammock is allowed to rest on the soft mulch of sea grass fragments. The ropes are attached around driftwood branches buried crosswise to the direction of the rope and covered with a small cairn of stones for extra stability. I don’t find tent pegs useful in kayak camping, except in proper campsites, also they are not permitted in aircraft cabin baggage. The dry sea grass also serves well as a toilet aid, the spiny plants of the maquis being unsuited to the task.

West and north of Girolata stretches the Scandola national park. Here a rhyolite volcanic flow has split into hexagonal columns as it cooled perpendicular to the cold surface of the solid rock which it has invaded. There is a good account of the geology of this coast at www.alpesgeo2003.fr/1 cr sorties/crs-corse/D11 LA CORSE GEOLOGIQUE.htm (note the spaces in the URL).

The cliffs remain impressively rugged, though with a different weathering pattern.

In semi-sheltered places the vertical cliffs support a shelf of algae, Lithophyllum, just above flat sea level which secrete a calcite support structure against the waves. This picture is about 2 metres across.

Our lunch in a shady grove behind the beach was disturbed by a park ranger who told us that we were not allowed to wander beyond the beach. Catherine secured permission for us to finish our lunch in the shade, exercising her essential third function, as diplomat.

By evening, we were out of the park area, resting on a deserted beach. The low scrub on the low rubble cliff was more promising than it appears: I could sling my hammock within the Arbutus forest.

The red sack was left as a marker so I could find my resting place after the usual dinner in the dark.

After setting up our tents we had time to relax over a cup of beer or coffee, and wait for the light to fade as the signal to start dinner.

The next morning we turned the corner into the gulf of Galeria, with the high mountains behind, still with traces of snow.

The weather was now completely calm. In the many lagoons there were fish and sea anemones, here with a curious papery flower. The picture is about 80 cm across. Sea birds were curiously sparse, though we passed a couple of sea eagle nests perched like chimneys on the top of inaccessible sea stacks.

We landed in Galeria for water and refreshment. We took the refreshment in the convenient cafe in the background. The village is tiny, though expanding with modern holiday villas.

Our next shore leave involved our only portage, across a gravel bar screening a fresh water lagoon fed by the river Fango.

The lagoon hosts a colony of turtles. The wetlands of Riciniccia have a rich and protected wildlife.

The person lecturing us about the extreme sensitivity of the wildlife runs a sit-on-top canoe hire business. After a long discussion, we agreed on paddling the river in small groups.

Those on land meanwhile enjoyed a shady lunch on park tables.

I took a walk along the river bank, enjoying the late flowering Cistus and gigantic Eucalyptus, though surely younger than Roman age.

and I met a huge cicada, 12 cm long.

We paddled on to our last beach bivouac in the bay of Crovani. I tried to fasten my hammock between the granite outcrops but found the rock extremely friable and deeply weathered, so settled for the safety of a soft carpet of flowers for the night. The fleshy leaved flowers are abundant, they are called witches fingers Carpobrotus acinaciformis and are native to South Africa, so I had no bad conscience, nor anxiety, as I lay just sheltered by the mosquito netting, but I had to pack my sleeping bag wet with dew.

Rising northerly wind was forecast from midday, so we broke camp at dawn for the unprotected paddle northward along the unbroken 7 km of granite cliff stretching to cape Cavallo. We then had time for a short break in the deep indentation of the bay of Nichiareto, then continued north to inspect the Grotte des Veaux Marins (seal cave).

There were no seals but a lot of disturbance in the water because a group of scuba divers was searching in the dark depth for a lost face mask.

The short break, and no lunch in sight, had taken their toll of my energy. I was beginning to feel tired as we rounded La Revellata, the north west corner of Corsica.

From there it was a downwind paddle over open water to Calvi.

Calvi is the most considerable settlement on our trip. It has impressive fortifications protecting impressive ancient buildings. Now its main street is entirely tourist gift shops and bars.

At Calvi we had our farewell lunch in a cafe overlooking the citadel.

It was excellent food, and very welcome after our unusually hasty and strenuous paddle of at least 25 km (maybe I will later be able to add the accurate figures from GPS owning companions).

Now it was time for the national groups to part. We embraced our French companions with warm appreciation of a relaxed and friendly adventure shared, with limited overlap of language but with great good humour.

The scariest part of the journey was yet to come. The road back to Ajaccio is spectacular, carved out of vertical cliffs at the approach to Porto. The goats nonchalantly spread out over the road added to the drama of the journey.

I returned to my home in Devon via Nice. This picture of the harbour shows the other end of the marine tourism spectrum. Twin boobs seem to be required decoration for the boats of the super-rich. I much prefer the subtler enchantment of paddling among rocks in the smallest boat devised by man.

My thanks to Cors’ Aventure (www.corse-aventure.com) for providing us with kayaks in perfect condition and for providing the excellent and varied food which made the trip so unusual, and thanks to our guide and cook, Catherine, whose charm and tact concealed a firm leadership. Thanks also to the organisers of the Bays Trophy (tropheedesbaies.free.fr) for planning this dramatic voyage round some of the most extravagantly sculptured coastal scenery on earth. And finally thanks to the weather god who was merciful, after the initial blast.

Tim Padfield

There are more pictures here: http://www.padfield.org/tim/kyk/tours/corsica2011/

Please write corrections and additions as comments – tim