CONSERVATION OF IRON: TREATMENTS AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES

Iron rusts when it is exposed to water and oxygen. The process is quicker

in the presence of salts, sodium chloride for example. Buried iron objects

are changed partly or entirely to corrosion products, which obscure the

object's original appearance. Significant traces of the original surface

may lie within this corrosion. The conservator's job is to stop or delay

further deterioration and to reveal the original surface, if it is safe

to do so. The processes used by the conservator alter the object's appearance

and may also change its physical and chemical structure.

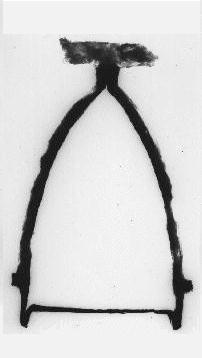

X-ray photographs are a great help to the conservator and are used

extensively in this exhibition. Uncorroded iron appears dark on the image

and heavier metals used for decoration, such as silver on iron, appear

even darker.

Stirrups represent a relatively homogeneous group of objects.

We can use them to illustrate the development of conservation techniques

and conservation ethics during the last 150 years.

The stirrups shown in the following pictures were found together in

1849 and were conserved by V.F. Stephensen, Conservator at the National

Museum from 1867 to 1908. They were re-conserved by Rosenberg in 1911.

Some have been treated again in modern times. The evidence that we have

suggests that they all looked alike when they were found.

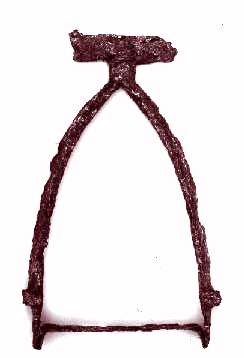

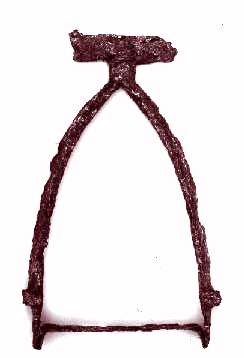

This stirrup (from Thorshøj) was first simply smeared with linseed

oil putty. Rosenberg treated it later in alternating baths of warm and

cold distilled water, until there was no trace of chloride (salt) ions

in the water. After that it was brushed clean and immersed in molten paraffin

wax, according to Krause's method of 1882. It has not been cleaned or treated

since. As a result the stirrup can still, 100 years after it was found,

be studied by archaeologists as a well conserved object.

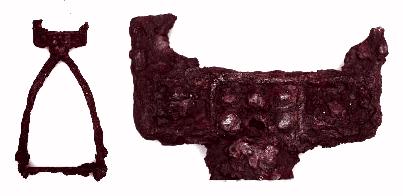

An x-ray picture of the stirrup, with a close up of the upper part.

The silver ornamentation can be seen preserved within the corrosion layer.

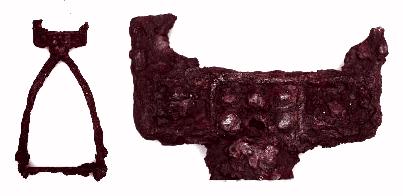

An aggressive treatment can spoil the possibilities for future investigations.

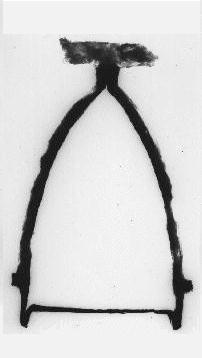

Stephensen treated this stirrup with acid. He boiled it in sulphuric

acid until a white scum formed. Rosenberg re-treated the object electrochemically,

according to Krefting's method of 1892: The object is surrounded with granulated

zinc and immersed in sodium hydroxide solution until the corrosion is removed.

The result: Rosenberg remarks in the margin of the museum's register: "...almost

no surface left."

All corrosion and ornamentation has vanished. Only the iron core is

left (x-ray picture on the right).

Next showcase....